that's love

During the eighteenth century, both men and women proved their romantic devotion with a homemade tattoo of their beloved's name, plus the word inochi, "life." The last stroke of the word was extended to suggest lifelong commitment.

During the eighteenth century, both men and women proved their romantic devotion with a homemade tattoo of their beloved's name, plus the word inochi, "life." The last stroke of the word was extended to suggest lifelong commitment.

I now live in Somerville with two females. Compare their shower paraphernalia:

with mine:More on this new living arrangement soon.

I'm not going to say "please." I don't say the word, and I wouldn't recommend saying it, either. Too often I hear people automatically saying "please"; the thoughtlessness of that habit just becomes grating to hear after a while. I usually hear the word when someone is ordering food: "I'll have a blah-blah sandwich, please. With ketchup, please. Yes, please." Enough of that! The server isn't going to withhold the food if the customer doesn't say please.

Yes, I know that it's supposed to be basic manners and courtesy, but when manners become rote repetition, what meaning do they have? The way I see it, there's no need to add politeness modifiers onto a request. Just be clear about what you want from someone, and then it's the other person's decision whether to go along with your request. If somebody needs a flowery word like "please" to sweeten the deal, well then, screw 'em. First it's "please," then it's money, and then what? It's a slippery slope of relinquishing your free will!

Well, maybe not. The point is not to speak out of habit. Even though I don't say "please," I try to say "thank you" when it's appropriate. You just made me a burrito? Thank you. You sold me a widget? Thank you. But you've really got to mean it when you say it. The truth is, I don't say "thank you" nearly enough as I should. People help me all the time, despite not saying "please," yet I'm not thoughtful enough to appreciate their compassion. Perhaps "thank you" isn't necessary, as long as I somehow appreciate someone's compassion. The trick, I suppose, is being thankful without letting "thank you" lose meaning.

The funny thing is that even though I don't say "please" in normal conversation, I try to say it in Japanese during Judo practice. Apparently, there's a tradition of saying "お願いします。" (onegaishimasu) before sparring with somebody of a higher rank. onegaishimasu is roughly, "please," but it's more complicated because it's used in different contexts, and it's more formal. In Judo, it means something like "please teach me" or "I hope our time together goes well." It makes sense that a lower-ranked judoka might have to make a polite request to a black belt in order to train with him (at least in Japan's class-conscious culture). Although I basically never hear it at the dojo, there's a particular black belt who said it to me before sparring, and after I looked up the meaning, I started saying it. It seems like a really great thing to say: onegaishimasu and bow, then let's beat each other up! It means, "I pray to you" to teach me, by throwing me on the ground. And since I don't know Japanese, it's hard to say onegai shimasu flippantly. I've got to think about it before saying it. If I say it, I've got to mean it. "I beg you to teach me!" — yes, even the lowly beginner who doesn't know anything. "Please teach me!"

I'm sure that if I lived in Japan I would get used to saying all sorts of wacky things depending on what kind of person I was speaking to, and frankly, I'm glad that we don't take politeness to the extreme that other countries do. But our weakness is that we invented a simple word to express a huge range of emotions, from "ketchup, please" to "please stop stabbing me!". The word's simplicity, and our training in politeness, make us less authentic. Politeness becomes a cheap façade, while we forget to be genuinely appreciative. I say, forget about "please."

onegaishimasu

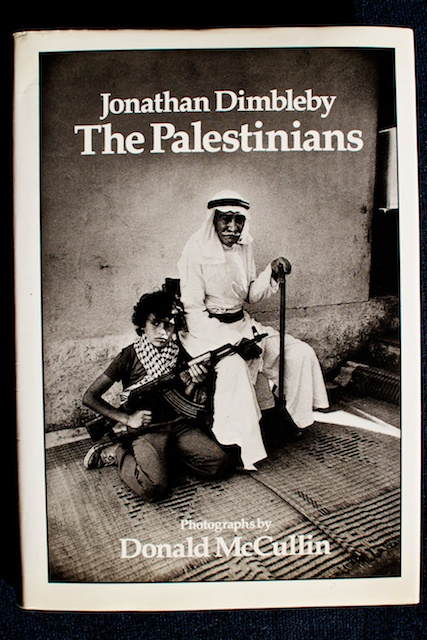

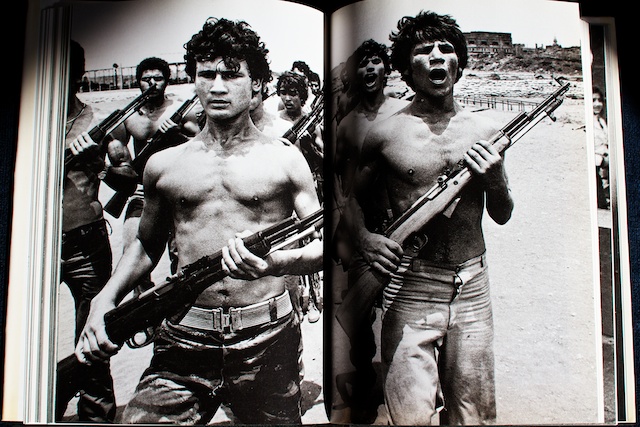

Yesterday I found a copy of The Palestinians by Jonathan Dimbleby at Lorem Ipsum Books. Published in 1980, it seems to be a little-known book that's long out of print, but I was excited to see it because I borrowed this book from a library years ago when I first heard about Don McCullin. The book contains 125 photographs from McCullin, including his widely-published photo of the aftermath of a phalangist murder of a palestinian girl.

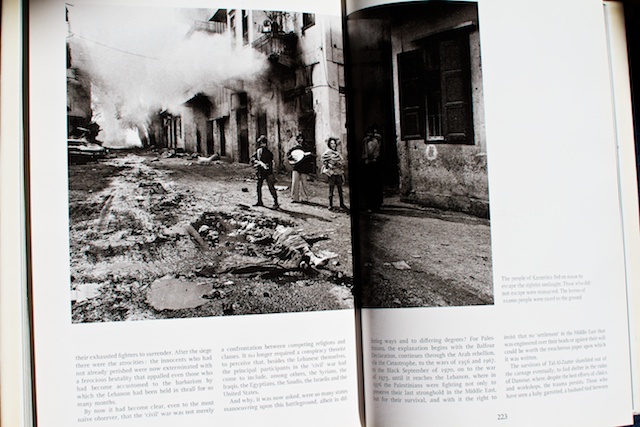

Some of the compositions are spoiled by a liberal use of double trucks, and the reproduction quality of the black and white photographs is a bit low.

In the case of the 'Palestinian problem', it is particularly difficult to represent reality, even if it may be more than dimly perceived. Merely to describe the Palestinians as a people with a past, a present and a future is to call into question some of the popular assumptions from which the prevailing strategies of the state of Israel derive their justification. To go further — to pay attention to Palestinian accounts of their own history, to record the impact upon them of the rise of Zionism, to relate their stories of the exodus, the exile, and the resurgence — is for the reporter to risk finding himself in the dock, charged by an articulate lobby with being an enemy of the people of Israel, if not an anti-Semitic racist.

The most obvious symbol of this distortion is the use of the term 'terrorist' to distinguish Palestinian from Israeli atrocities. 'Terrorists' do not have jet planes to mutilate innocents from a distance; they do it with bombs in markets. Is the former less heinous than the latter because it is sanctioned by an Israeli Cabinet? Reason and morality answer 'No', but again and again the Israeli authorities emerge morally inviolate from their military adventures while the PLO is compared to the Nazis or the Ku-Klux-Klan for refusing to give up guerrilla war.

To tolerate this imbalance is to beg the central question to which all others lead: to whom does Palestine belong? This is a reporter's book. It does not argue a case, nor does it propose a solution. It merely attempts to give an account of their 'problem' as it is perceived and experienced by the Palestinian people.

And that introduction sets the tone for an unapologetic account of the history of Palestine and the creation of Israel, from a British point of view. First, if this book were written today, would it be forced to "present both sides of the issue" equally for fear of bias complaints? It even surprises me to read such a casual description of Zionism's history as the one recounted in the book; today's media has trained me to believe that evoking Zionism as a motive for Israel's aggression is akin to saying that the moon landing was a hoax. Maybe there's something to the fact that both the author and photographer are British — they have an obligation to criticize the situation because it was their empire that screwed up the region in the first place. Whatever the case, 30 years later, America still has a distorted relationship to Israel that, I think, would prevent The Palestinians from being published here today.

Second, even from the bits I've read so far, I'm depressed by the intractability of the problem. Portions of the book speak about events that could've happened yesterday rather than 30 years ago. Of course, the book couldn't have predicted Mossad's practical creation of Hamas, but it ends with a long quote from a now-irrelevant prominent Fatah member, Salah Tamari:

'I want to add something which is most important for me. If you ask a well-educated liberal Jew, "Are there Palestinians?" he'll say, "Yes, of course." He will also acknowledge that we have lived in Palestine for many hundreds of years. And if we ask, "Do they have the right to live in freedom?" he'd of course say, "Yes." "Should they not be permitted to return to their homes then?" At this point his loyalty to the state (the Jews are brought up in the Germanic tradition of greater loyalty to the state than to the individual) conflicts with his sense of justice, and he will say, "No." That is why we have to fight.

...The Jews have had a very painful experience, and because of the great influence of their religion and the impact of Zionism, they have led themselves to believe that they are only safe inside the Zionist state. Outside that state they believe they will meet persecution.

'The Jews inside Israel are riddled with fears. They're afraid of the Arab population growing in Palestine and outnumbering them; they are afraid of the inevitable progress of the Arab states which encircle them; of the growing might of their armies. So they gamble on the weakness of the Palestinians, on disarray in the Arab world, on the influence of America, and on the guilt complex of the West. And they recognize that all this is a dangerous gamble because these are all temporary factors.

'If only they could understand that our conflict is not with them, not with the Jews, but with the Jewish state. It may seem unrealistic but we believe that, as the conflict continues, the Jews in Israel will cease to believe in the sanctity of their state. We believe that their mentality will change, that they will begin to accept that the future cannot lie in an artificial, racist state, but in a new natural state in which Jews and Arabs live together in equality. But we can only persuade them of this if we are strong. We are obliged to fight.'

It's cliché to say "the more things change, the more they stay the same." Instead, I'll just wave my imperial American hand and say that the whole middle east is fucked, then I'll put The Palestinians back on the book shelf and reach for a more uplifting photo book — something by Anne Geddes should do.

What is it about Boston that turns people so cold? Look at people on the street or on the T, and they're either staring into their phones or else averting their eyes. When I see people staring nervously off at nothing, I imagine them thinking, "ok, pretend that you see something over there. Yup, that's it — don't look at anyone else." Everybody is in his own little bubble, trying desperately to keep up the illusion that there aren't thousands of other people living right around him.

Another thing I notice is that people who are outside are rarely outside just to hang out. They're on their way to somewhere very important, and if teleportation existed, I'm sure the streets would be nearly empty aside from the bums. Sure, some folks hang out at grassy areas in the sun, but they are the exception, and even then, they're often using their computers. Who just wanders around anymore? Who walks and takes the time to appreciate the world around us?

In nice weather, I used to pace up and down Mass Ave for hours, just observing, paying attention. Even if I never took a picture, it was still worth doing. It was my way of being in the world. Now, that practice is discouraging to me because I notice how estranged we are from each other.

I met a 90 year old photographer in Stockbridge who remarked that people there just walk down the street obliviously looking at their own shopping bags thinking, "Oh, look what I bought." His words rang true, although around here, people might be thinking, "Am i there yet? Get me off this street."

What about photography? Well, forget about it in Boston. I hadn't thought about how particularly bad this city is for photography until a teacher recently confirmed my suspicions — apparently, even famous photographers from the area refuse to work here because the people are too uptight. Actually, I don't know what the issue is, but it must be some kind of paranoia. A few weeks ago, I saw a well-dressed business woman walking toward me, eating an ice cream cone (a playful scene, if obvious). As I raised the camera to my eye, she yelled, "No! No!" and put her hand up. Yikes! Ok. Another guy, after I took his picture, stumbled a bit and looked shocked, as if I had stabbed him.

Although I genuinely do not understand this response, I think that some photographers share the blame for this collective paranoia. I see many sneaky photogs who shoot from the hip or from across the street, almost like peeping Toms. At one outdoor festival, I witnessed one guy moving through the crowd, discreetly taking shots of girls' cleavage. Nice for him, I suppose, but I think that as discreet as he was, there's still the sense that he's a creepy guy being sneaky with a camera. He gives us a bad reputation.

These days, I'm even concerned about how I hold my camera. I usually hold it facing down, with my finger on the shutter button, but then I notice people looking skeptically at me and the camera, as if I'm shooting their butts or something. I've experimented with walking around with the lens against my cheek, indicating that I'm not secretly photographing anybody. I think that helps, but it's tiring. If only they knew that if I wanted to make a picture it would be quite obvious what I was doing.

People seem to think that someone wielding a camera is out to steal something from them. What is there to take? What secret do you think I can see? Beats me. Even the most visually boring person in the world looks quizzically at my camera, seemingly thinking, "Uh oh, did he get me? What's he up to?" I want to say, "Don't worry, you are incredibly boring, and just because I have this camera doesn't mean I want to make a boring picture of you. Carry on."

Other places are more friendly to photographers. New York takes the cake — cameras are deeply understood, and besides, everybody there wants to be a star. I do not know what went wrong with Boston. Maybe puritanical modesty persists in the water here...

Back to the sneaky photographer issue: it really bugs me. I recently saw photo on Flickr by a local photographer. It was a photo of a homeless veteran with a caption that said something along the lines of "this man must have a story to tell. I don't know what his story is, but blah blah blah" followed by a paragraph about war and veterans or something like that. I left a comment saying that if the photographer wanted to know the guy's story, he or she could've talked to him, considering the guy was sitting just feet away. Furthermore, I commented about this photographer's tendency to shoot people from 20 feet away, as if the subjects are going to bite. I tried to say (in a constructive way) that getting closer and maybe engaging the subjects will lead to better photos. Certainly if the intention is to tell someone's "story," then the photographer needs to get closer and be less sneaky.

Well, the photographer was upset with my remarks, deleted my comment, blocked me from commenting further, and replied, "You must disagree with my opinions about war. You must be a veteran. Yadda yadda... Never before has somebody criticized me like that on Flickr. How patriarchal, yadda yadda." Then I remembered another thing my teacher was adamant about: don't waste your time on Flickr. If you've got a community of photographers whose typical comment is "nice capture!", I think they're all doomed to mediocrity.

Photographers of life need to create order from chaos, to edit out the irrelevant crap and show us why we should care about the things in the photographs. Photographs should ask questions, but not too many as to make the meaning indecipherable. Photography may be democratizing, but the act of photographing requires a kind of ruthlessness: why choose this moment and not some other? What is so special about this 1/250th of a second that I'm supposed to see? A photographer who hasn't thought through these things needs to keep working. A photographer bears a lot of responsibility. We can't screw this up.

I need to see harder than I have been seeing. I have only this lifetime to get it right.